The disqualification clause of the 14th Amendment is seldom used and raises novel legal questions

SCOTUS' response to oral arguments made by Colorado's lawyers is highly critical of the removal of Trump from ballots

…the few times it has been used in the past mainly arose out of the Civil War — a very different context from the events of January 6. It is therefore unclear to what extent historical precedents provide useful guidance for its application to the events of January 6.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) is a nonpartisan public policy research arm of the United States Congress. It is part of the Library of Congress and provides Congress with comprehensive and reliable research and analysis on a wide range of topics to support the legislative process.

CRS is comprised of a team of highly skilled policy analysts, attorneys, and other experts who are dedicated to providing objective and authoritative information to Congress. Their primary function is to ensure that members of Congress have access to the information they need to make informed decisions on policy issues.

The information provided is largely sourced from a CRS report that had a recent update back in 2022.

At the end of this article I included a short summary of the oral arguments made to SCOTUS regarding Colorado’s removal of Trump from the ballot, and what the Justices’ general outlook seems to be. You can also find the full 2 hour audio of the hearing at the end of this article.

Thanks for reading! I hope you enjoy.

A ‘brief’ history on Section 3

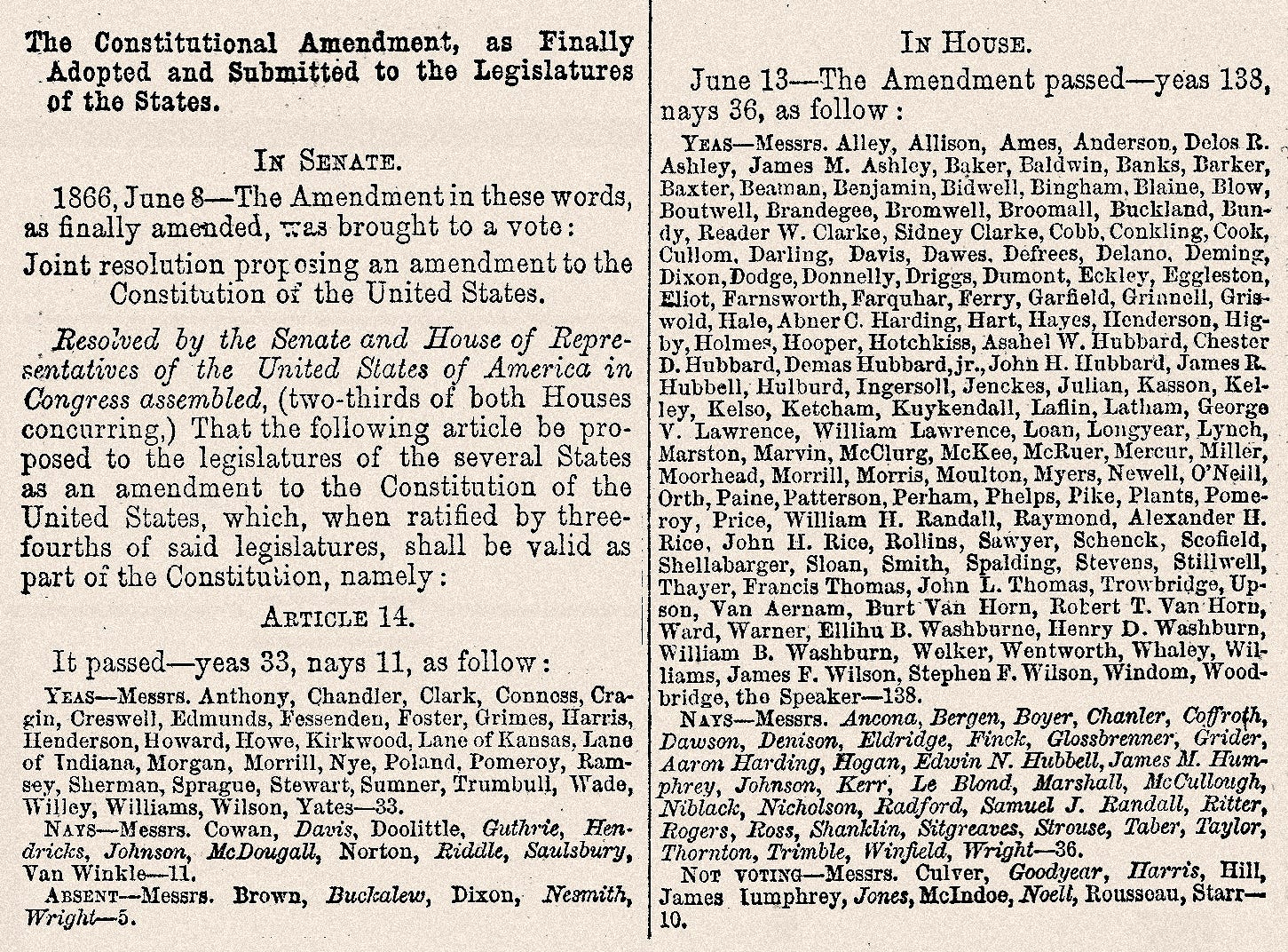

The history behind Section 3 of the 14th Amendment is rooted in the aftermath of the American Civil War and the efforts to reunite the nation while addressing the consequences of the conflict.

During the Civil War, many government officials, military officers, and others in positions of power in the Confederate States of America actively participated in the rebellion against the United States. After the war ended, some of these individuals attempted to regain their positions in the government.

In response, Congress passed the 14th Amendment which included Section 3 to address this issue.

The primary purpose of Section 3 was to ensure that those who had betrayed the United States during the Civil War would not be able to regain power and potentially undermine the Union's efforts to rebuild and reunify the nation. It was also intended to discourage future rebellions by making it clear that there would be consequences for those who participated in such actions.

Section 3 was for the most part used only for the short period between its ratification and the 1872 enactment of the Amnesty Act. The Amnesty Act removed the disqualification from most Confederates and their sympathizers and was enacted by a two-thirds majority of Congress in accordance with the terms of Section 3.

The Thirty-Ninth Congress convened in 1865 with various Confederate leaders from the Committee on Reconstruction explaining in its report, the elections in the South "resulted, almost universally, in the defeat of candidates who had been true to the Union, and in the election of notorious and unpardoned rebels... who made no secret of their hostility to the government and the people of the United States." The Joint Committee thus recommended "the exclusion from positions of public trust of, at least, a portion of those whose crimes have proved them to be enemies to the Union, and unworthy of public confidence."

Questions were raised in these hearings concerning the staggering number of those affected by the proposal, totaling an estimated fourteen thousand as Representative James G Blaine recalled in a memoir.

During the Senate proposal hearing, one Senator argued exclusion would make ratification of the 14th Amendment “impossible in the South,” while another stated concerns that following through would further divide. “Do you not want to act upon the public opinion of the masses of the South? Do you not want to win them back to loyalty? And if you do, why strike at the men who, of all others, are most influential and can bring about the end which we all have at heart?”

The response to these objections by the Joint Committee was, "Slavery, by building up a ruling and dominant class, had produced a spirit of oligarchy adverse to republican institutions, which finally inaugurated civil war. The tendency of continuing the domination of such a class, by leaving it in the exclusive possession of political power, would be to encourage the same spirit, and lead to a similar result."

On July 9, 1868, Louisiana and South Carolina voted to ratify the 14th Amendment, making up the necessary three-fourths majority.

Other than the Confederates Section 3 was applied to, the disqualification clause has seldom been used.

Congress last used Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1919 to refuse to seat a socialist Congressman accused of having given aid and comfort to Germany during the First World War, irrespective of the Amnesty Act. The Congressman, Victor Berger, was eventually seated at a subsequent Congress after the Supreme Court threw out his espionage conviction for judicial bias. Recently, various groups and organizations have challenged the eligibility of certain candidates running for Congress, arguing that the candidates’ alleged involvement in the events surrounding the January 6, 2021, breach of the Capitol render them ineligible for office.

In addition to this relatively recent application, a New Mexico state court removed Otero County’s Commissioner, Couy Griffin, from office, and barred him from seeking or holding office based on his alleged participation in what took place on January 6th.

Several other states have taken action to remove former President Donald Trump from their ballots. These states include Colorado and Maine, where their respective Supreme Courts have ruled that Trump is ineligible to appear on the primary ballot, citing the 14th Amendment's insurrection clause.

However, it is important to note that these decisions are currently on hold as they are being appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The outcome of these appeals will ultimately determine whether or not Trump remains on the ballots in these states. Maine has decided to defer to whatever ruling SCOTUS hands down. Oral arguments for the Colorado case were just heard by SCOTUS last week.

There are also other states where similar efforts to disqualify Trump from the ballot are underway, such as California, New Hampshire, and Michigan. The results of these efforts are still pending, and it remains to be seen whether they will be successful in removing Trump from the ballot in these states. A decision from SCOTUS on the Colorado case could very well determine the fate of these efforts.

Historians continue to discuss the deep questions raised by this section regarding the meaning of representation, the way we seek to reunite our society, how focused the intent of Section 3 actually was, and whether this clause can be used today.

(Sorry, I know that wasn’t very brief.)

Who does Section 3 apply to?

The question of whether or not the President and Vice President are included in the scope of the disqualification clause has been widely debated. Many argue that the text of this clause clearly excludes the President and Vice President as the manner in which they were mentioned references “electors of” rather than simply stating each position.

Section 3 of the 14th Amendment:

No Person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

The Impeachment Clause of the Constitution is much more explicit in its text and is a core component to the questions raised surrounding who Section 3 applies to. The argument is that there is a clearly defined difference between the President, Vice President, and “all civil officers.”

Article II, Section 4:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

Counter arguments to this suggest that the text also states, “…or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States,” thus establishing the Presidency would constitute a civil or military office.

It is still unclear which direction SCOTUS will rule with respect to this, if at all, as there are no historical examples of this clause being used to bar someone from the Presidency. However, there is reason to believe SCOTUS is leaning towards an interpretation that this wouldn’t apply to the presidency based on their statements made during the recent hearing regarding Colorado’s case against Trump.

How might this clause be triggered?

The first notable point in this section is that the Constitution does not define insurrection or rebellion. It is believed that Congress holds the power to define insurrection based on Article 1, section 8, clause 5, of the U.S. Constitution which empowers Congress to utilize armed forces to suppress insurrection. It also authorizes the President to call upon armed forces to ensure “unlawful obstructions … or rebellion” that impede the enforcement of U.S. laws. However, SCOTUS has observed that the Insurrection Act would need to have been invoked by the President for the existence of an insurrection to be recognized for disqualification purposes.

Despite this, it’s not necessarily required when considering the Constitutional powers Congress has.

Two constitutional powers also arguably authorize Congress to determine the occurrence of an insurrection by legislation: the Militia Clause and Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Militia Clause (Art. I, § 8, cl. 15) grants Congress the authority to call forth the militia to “suppress Insurrections.” Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides Congress “power to enforce [the Amendment] by appropriate legislation.” A legislative determination that an insurrection occurred pursuant to one of these constitutional authorities would likely at least be accorded judicial weight in the event of a prosecution for insurrection or any procedure Congress might put in place to determine disqualification under Section 3.

Another hurdle to overcome following the establishment of an actual rebellion or insurrection would be determining whether a specific person was engaged in such activities. Section 3 does not establish a procedure for determining who is subject to it, instead it establishes the means for removing the disability, leaving this particularly relevant step in wielding this clause against Trump likely to fail.

The only “sufficient proof” the report cites for determining this are two statutes:

The insurrection statute, 18 U.S.C. § 2383

Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.

The treason statute, 18 U.S.C. § 2381

whoever, owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them . . . is guilty of treason . . . and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.

These things considered, Congress would likely have to enact legislation to execute section 3 with the intent of barring someone from running for, or becoming President.

It also suggests, as it stands, there is only one real mechanism for disqualifying a Presidential candidate — that being a conviction under one of these two statutes.

What does SCOTUS think?

The Supreme Court's response to Colorado's lawyers' oral arguments regarding the removal of former President Donald Trump from ballots under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment was critical, with some justices expressing skepticism and others raising concerns about the implications of such a decision.

During the oral arguments, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Neil Gorsuch questioned whether the Colorado lawyers were correctly applying Section 3 of the 14th Amendment and whether it was intended to apply to former presidents. They also raised concerns about the potential expansion of state power over federal elections.

Justices Elena Kagan and Amy Coney Barrett posed tough questions to the attorneys representing Colorado voters, asking about the practical implications of their arguments.

There seemed to be somewhat of a “consensus” amongst some Justices that the textual interpretation of Section 3 suggests the former President cannot be disqualified as it is not referring to the Presidency. The reasoning is that it lists each office holder that would be subject to this clause, and the President is simply not listed. They specifically asked Trump’s lawyer why he didn’t include this specific argument in their filing.

It appears they may also be leaning towards an interpretation that would dismantle this idea that States can impose their individual will on the entirety of the Nation, suggesting that one single state having the ability to disqualify a presidential candidate would be disenfranchising, and the consequences of doing so would be on a national or federal level. They also questioned Colorado’s lawyer as to how they would reckon with the incongruence between various States’ rulings regarding Trump’s candidacy.

Additional complex positions were argued by each side that are worth diving into. If you’re interested, you can listen to the full recording of the oral arguments made before SCOTUS on February 8th, 2024, via the embed below.