First Steps Into Gatsby: Experiencing Ballet’s American Dream

Washington Pavilion, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA

First Steps Into Gatsby: Experiencing Ballet’s American Dream

It began, as the best nights do, with running late.

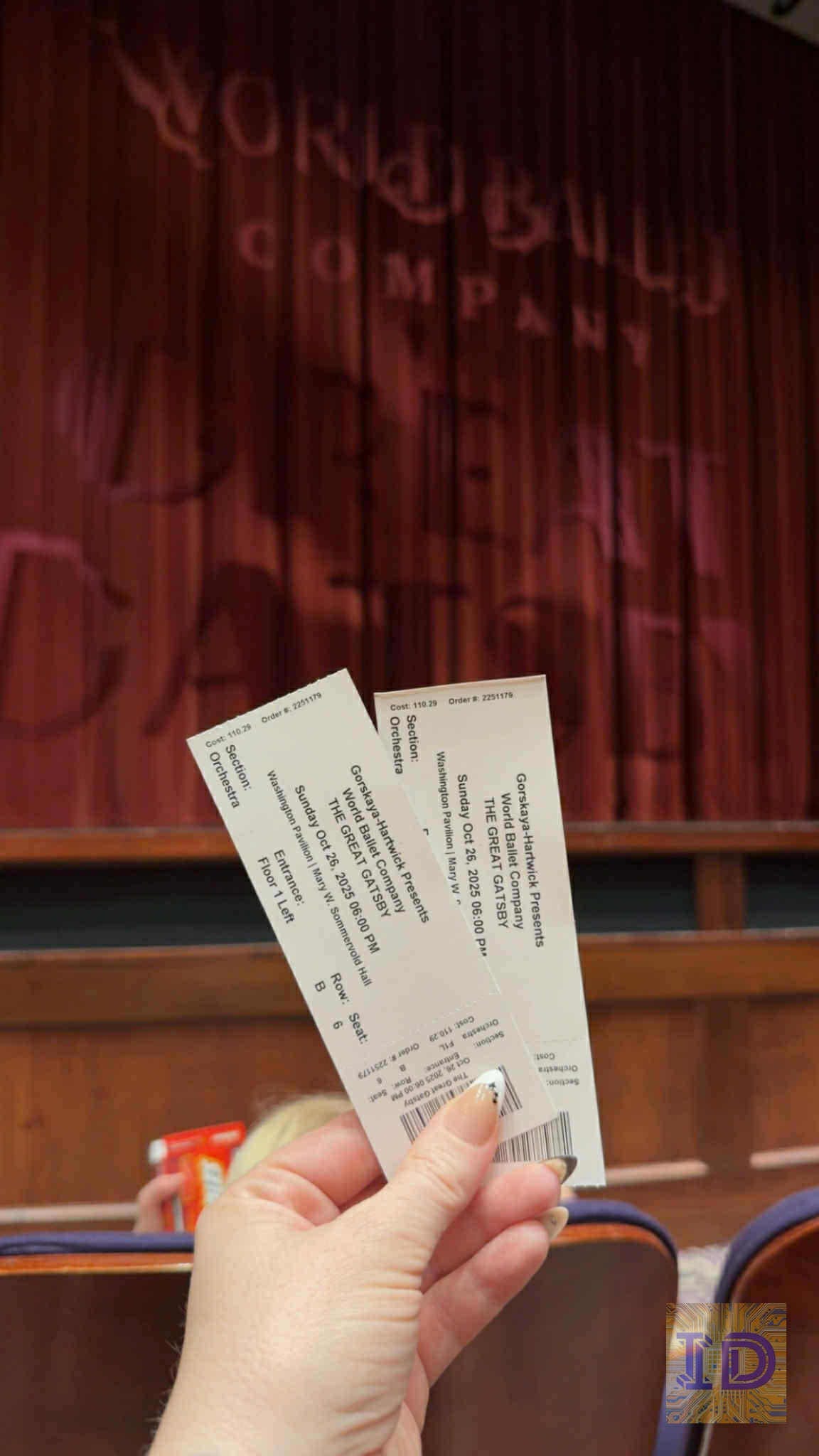

Dinner at Harvester’s had unfolded like a compressed miracle — a five-course dash served with quiet precision so that my best friend Emily and I could still make the 6 p.m. curtain at the Washington Pavilion, that grand quartzite heart of Sioux Falls’ arts scene.

By the time we slipped through the doors, the lights had already fallen and the first strains of music — lush, cinematic, deceptively live — were flooding the hall. Somewhere across town, my husband was watching The Great Gatsby film, while I stepped into Fitzgerald’s world through motion instead of words.

A Jazz Age without dialogue

This World Ballet Company production, choreographed by Ilya Zhivoy with a shimmering score by Anna Drubich, retells the novel through gesture alone. The story is visible in the body: Gatsby’s reach, Daisy’s recoil, Nick’s hesitation. No dialogue — only the dancers’ unspoken grammar of regret and hope.

Emily, more observant than I, later pointed out what I had only half-registered. The costumes were breathtaking, threaded with texture and gold, catching the light in ways that made the 1920’s come alive from every corner of the theater. She loved the unexpected acrobatics — how bodies turned the stage into a kind of living architecture — and the comedic timing that somehow found humor in a story famous for tragedy.

And then came the twist neither of us expected. A ballerina who sang live. Her voice cut through the music like a spotlight, merging ballet and cabaret in one aching moment. Emily leaned over, whispering that she’d never seen singing in a ballet before. Neither had I.

Gold, laughter, and illusion

Between acts, we circled the Pavilion’s marble atrium, running into friends who’d soon hand us their front-row seats. The second half transformed with proximity. What had been broad tableaux became intimacy — sweat glinting under stage lights, facial expressions layered with irony and ache.

From so close, the projections behind the dancers became their own character. Gatsby’s mansion flickered into view like a memory reforming in real time. Emily was mesmerized by the detail. How the digital gold touched everything. How reflections shimmered like liquid champagne across the scrims. The effect wasn’t gimmickry — it was poetry rendered in pixels.

The dream and the decoding

We both agreed afterward that you had to know the story to follow the plot fully. Without context, the relationships might blur, though the emotions never did. Still, the performance’s humor, athleticism, and rhythm gave the audience something universal to hold on to, even for those unfamiliar with Fitzgerald’s doomed world.

When the final tableau froze — Gatsby forever reaching for that elusive green light — the applause rose like surf.

After the gold fades

Later that night, as my husband recounted Baz Luhrmann’s film version, I realized how perfectly our evenings had mirrored each other. His Gatsby awash in camera angles and pop anthems, mine unfolding in the near-silence of bodies in motion. Both were glittering illusions about wanting more than life allows.

For Emily and I, that night wasn’t just about dance. It was about the shared astonishment of how gold light, humor, and heartbreak can coexist on a single stage. The Great Gatsby Ballet turned a late dinner and a borrowed pair of tickets into something luminous, fleeting, and unforgettable.